This blog entry is a repost from Dominick Shattuck, PhD, on his Substack. You can follow along and subscribe via the following LINK.

Boys Falling Off the Health-Care Map:

And How We Keep Them Connected

Original Post: Dec 27, 2025

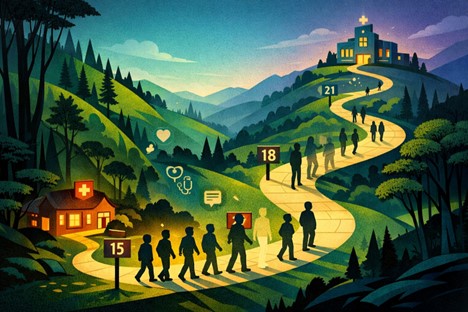

When we talk about “kids and health care,” it’s easy to picture a straight line from pediatrician to adult primary care. The latest research from Akande and colleagues (2025) says that’s not what’s happening, especially for boys.

In a new study in the Journal of Adolescent Health, Akande et al. (2025) track young people’s annual checkups from about age 15 to 23 and show that while many stay connected to preventive care, a substantial group of boys quietly disappear from the system altogether.

That’s not a minor blip in utilization. It’s the moment when future men exit care, taking their preventable heart disease, cancers, injuries, and depression with them.

Key terms

- Adolescents and young adults (AYAs): In this study, youth in the NEXT Generation Health Study followed annually from ages 15–23.

- Well-visit attendance (WVA): Routine, preventive primary care visits, annual checkups where vaccines, mental health, sexual health, and risk screening should happen.

What Akande et al. Found

Akande et al. use data from a nationally representative U.S. cohort (n = 2,766) followed annually for seven years. They apply latent class growth analysis to map distinct patterns of well-visit attendance over time, separately for males and females.

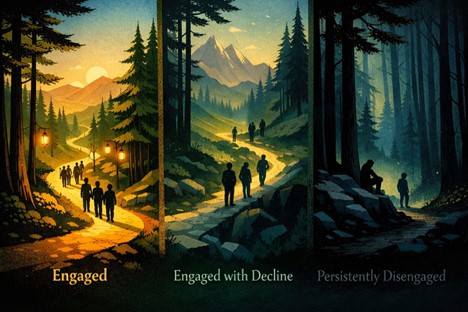

For boys (males), they identify three WVA trajectories:

- Engaged – 66% (n = 818): stay relatively connected to annual well-visits from 15 to 23.

- Engaged with Decline – 17.7% (n = 221): begin with higher attendance but drop off across late adolescence and young adulthood.

- Persistently Disengaged – 17% (n = 208): rarely attend preventive visits at any point.

For girls (females), the three classes look similar but importantly different at the margins:

- Engaged – 67% (n = 1,022)

- Engaged with Decline – 19% (n = 295)

- Gradually Re-engaged – 13% (n = 202): drift away but come back into care over time.

What’s the difference?

- There is a distinct, persistently disengaged group that does not appear among girls.

- While both sexes show declines, girls have a pathway back; disengaged boys are far more likely to not return to care.

This study also show that class membership has context. For example:

- Boys with chronic health conditions are significantly more likely to be in the Engaged class.

- For both sexes, WVA trajectories are significantly associated with health and insurance status, family affluence, race/ethnicity, region, and youth/parental nativity.

The system, in other words, hangs onto boys who are already managing illnesses, but loses many who “seem fine” until they are not.

“It’s Fine, I’m Fine”: Masculinity Scripts and Help-Seeking

The Akande et al. findings sit squarely in what men’s health research has been saying for two decades.

Leone and colleagues developed a conceptual model of men’s access to health care based on a survey of 485 adults, using the M.A.L.E. H.E.L.P. Questionnaire (MHQ) to map attitudes and behaviors that keep men out of care. They found that beliefs such as:

- “I don’t think anything is wrong with me,”

- “My health is only about me,” and

- “Most men in my family don’t go to the doctor”

are strongly associated with delayed or absent health-care use.

This logic shows up early. The persistently disengaged boys in Akande et al.’s study look like younger versions of the men Leone describes: low perceived risk, high self-reliance, and family norms that minimize preventive care.

Teo et al.’s (2016) systematic review of men’s health screening behaviors adds another layer. Across more than 100 studies, the most common barriers for men include:

- Lack of time

- Low risk perception (“no symptoms, no problem”)

- Fear of finding a disease

- Painful or invasive procedures

- Limited knowledge about screening

Masculinity-linked attributes like self-reliance, avoidance of femininity, heterosexual self-presentation, and “invincibility” beliefs consistently emerge as male-dominant barriers.

Mursa’s (2022) review of men’s help-seeking in general practice pulls this together at the service level: men often see general practice as unwelcoming and unaccommodating, and mostly as a place for acute problems, not prevention or lifestyle support.

For adolescent boys, this mix can look like:

- “If I’m still playing sports and going to school, I’m fine.”

- “Clinics are for little kids or for when something is really wrong.”

- “I can’t look weak or like I’m overreacting by going in for a ‘routine’ visit.”

Among the classes identified in Akande et al., the persistent disengagement class is exactly what we’d expect when those beliefs meet systems that don’t make preventive care feel necessary, relevant, or welcoming.

The Quiet Sorting: Which Boys Stay Linked to Care?

One of the strengths of Akande et al.’s analysis is its focus on who ends up in each trajectory. Through the the NEXT Generation Health Study, they show that WVA class membership is tied to:

- Insurance continuity and type

- Family affluence

- Race and ethnicity

- Geographic region (South, West, Midwest, Northeast)

- Youth and parental nativity

Leone’s (2017) model underscores how these structural factors interact with beliefs: men from lower socio-economic backgrounds, who may have fewer role models for preventive care, are more likely to rate their use of the system as “minimal” or “non-existent,” even when services are technically available.

Teo et al. (2022) also note that while individual-level barriers dominate, facilitators like partner encouragement, physician recommendation, and easy access to organized screening programs can pull men in.

Put together, Akande et al. and the broader men’s health literature suggest an adolescent sorting process:

- Boys with visible health needs (e.g., chronic conditions) get tethered to the system and become the Engaged class.

- Boys in more resourced families and communities get nudged along by parents who keep appointments, manage insurance, and see preventive care as normal.

- “Low-maintenance” boys—no diagnosed conditions, families with thin connections to health systems—slip into the Persistently Disengaged class with almost no friction.

Clinics rarely have mechanisms to notice their absence until those boys resurface with injuries, crises, or advanced disease years later.

Boys, Pressure, and the Digital Mirror

Akande et al. give us the utilization pattern, while recent articles work from the Pew Research Center fills in the social and emotional context.

In The Gender Gap in Teen Experiences, Parker and Hurst show that teens see anxiety and depression as top problems in their schools, and they see many of these problems as hitting girls particularly hard.(Pew Research Center) At the same time:

- Boys report more pressure to be physically strong and good at sports.

- Girls report more pressure to look good, fit in socially, and get good grades.(Pew Research Center)

These pressures align neatly with traditional gender scripts: girls as emotionally expressive and relational; boys as stoic achievers and performers. Not shockingly, girls are more likely to be seen as needing emotional support, while boys are more likely to be seen as disruptive and less likely to speak up in class.(Pew Research Center)

Pew’s report on Teens, Social Media and Mental Health adds the digital dimension:

- Most teens say social media helps them feel more connected to friends and lets them express creativity.

- Roughly 1 in 5 teens say social media sites hurt their own mental health, but a growing share say these sites harm people their age.

- Around half say what they see on social media makes them feel more accepted or like they have people who will support them.(Pew Research Center)

In other words, teens (boys included) are:

- Commonly using mental-health terminology and emotional content,

- Turning to digital spaces to process stress and find support, but

- Not necessarily translating that into formal help-seeking or clinic visits.

By the time they age into young adulthood, news and information habits shift again. In Pew’s data essay on Young Adults and the Future of News, adults under 30 are the least likely to say they follow the news all or most of the time, and the most likely to get news from social media. (Pew Research Center)

Accurate and balanced health content likely follows the same pattern: information has to find young men in their feeds, not the other way around. This information should come from credible sources and promote pro-social behaviors. Meanwhile, our care models still assume young people will proactively seek out in-person preventive visits on an annual schedule.

If you overlay that onto Akande et al.’s trajectories, the story is clear: the boys most immersed in digital coping, and least connected to institutional cues like school nurses or college health centers, are exactly the ones most at risk for persistent disengagement. (ScienceDirect)

Building Clinics Boys Come Back To

So what does all this mean for practice and policy?

The men’s health literature, and frameworks like Evans et al.’s Health, Illness, Men and Masculinities (HIMM) model, push us toward lifecourse, gender-responsive thinking. The HIMM framework emphasizes how masculinities intersect with social determinants across youth, mid-life, and older age to create health disparities. Adolescent disengagement from care is one early expression of that pattern.

Drawing on Akande et al., Teo, Mursa, Leone, Evans and others, we can outline a few design principles.

- Treat retention as a core outcome, not a happy accident

Akande et al. show that disengagement is not random noise—it’s a stable class structure over the transition from 15 to 23. (ScienceDirect) Health systems can:

- Track WVA trajectories by sex, race/ethnicity, insurance, and region at practice or network level.

- Flag adolescents, especially boys, who miss consecutive annual visits and trigger structured outreach (calls, texts, portal messages, school-based follow-ups).

- Use those patterns as performance indicators, not just raw visit counts.

- Reframe preventive care in boy-friendly language

Teo et al. highlight that low risk perception and fear of diagnosis are key barriers; facilitators include knowledge, perceived benefits, and clear recommendations.

For boys:

- Anchor well-visits in performance and future-oriented outcomes: energy, focus, sports performance, safe driving, getting and keeping jobs, rather than simply “finding out what’s wrong with you.”

- Talk about mental fitness alongside physical conditioning.

- Use messaging that frames checkups as what responsible, capable young men do for themselves and others.

- Fix the front door of care

Mursa’s review makes clear that general practice can feel unwelcoming and unaccommodating, with reception acting as a gatekeeper, limited after-hours appointments, and out-of-pocket costs that discourage preventive visits. For boys and young men, improvements include:

- Youth-friendly reception training and confidential booking options (online or via text) so they’re not explaining sensitive issues in a crowded waiting room.

- Extended hours and walk-in slots tied to school and work schedules.

- Promotion of telehealth and quick check-ins as legitimate entry or retention points, especially for mental health, sleep, and substance-use concerns.

- Start where boys already are—and turn one-offs into longitudinal care

Sports physicals, school-based health, urgent-care visits for injuries, and even digital encounters can be built into on-ramps for ongoing care:

- Every touchpoint becomes an opportunity to schedule the next well-visit before the boy leaves.

- Briefly explain the purpose of annual visits in concrete, in a variety of age-appropriate and appropriately worded messages to reach the variety of boys who will benefit.

- Use tailored reminders (e.g., “Staying cleared for sports,” “Keeping your concentration sharp”) that map onto what matters to that boy.

Teo et al. note that combining personalized letters with reminders and partner encouragement significantly boosts screening uptake in men; similar multi-channel nudges could support adolescent WVA.

- Make mental health an embedded, not separate, conversation

Sharp et al.’s focus group work on men’s mental health promotion emphasizes framing mental health in acceptable locations, contexts, and behaviors that align with masculine norms, while gently reworking those norms.

For boys, that can look like:

- Brief normalized mental health screens as routine parts of the annual visit (no special “mental health appointment” required).

- Conversations grounded in everyday anchors like sleep, gaming, social media, sports, school stress, rather than immediately in diagnosis labels.

- Offering concrete strategies (exercise, peer mentorship, structured groups) that sit comfortably with many boys’ sense of identity, while leaving room for more intensive support when needed.

- See adolescence as the first “men’s health” policy window

Evans et al.’s HIMM framework argues that masculinities and social determinants shape health differently at each life stage, and that youth is where patterns of risk and service use begin to crystallize. Akande et al. essentially give us an early-life retention dashboard: which boys stay in care, which drift, and which are lost.

Policy and planning implications:

- Embed adolescent and young adult retention metrics into quality frameworks for primary care.

- Resource school-based and community-based strategies that explicitly aim to keep boys connected through the 15–23 window.

- Ensure men’s health strategies treat boys’ retention in care as a core equity target, not a niche topic for pediatrics alone.

Why Losing Boys Now Costs Us for Decades

Evans and colleagues remind us that men, especially those facing social disadvantage, experience poorer outcomes across mortality, chronic illness, injuries, and disability than women with similar backgrounds. The familiar story that includes late presentation, low use of preventive care, and fragmented relationships with services doesn’t suddenly appear at 40. It starts when boys quietly drop off the map as teenagers.

Akande et al. show that:(ScienceDirect)

- Many adolescents remain engaged in well-visits.

- Yet meaningful declines occur for both sexes,

- And a unique subset of boys is persistently disengaged from preventive care throughout the transition to adulthood.

Those disengaged boys are tomorrow’s men who show up late, if at all, with complex, preventable conditions. If we care about men’s life expectancy, suicide rates, or chronic disease, we can’t afford to treat adolescent retention as an afterthought.

The takeaway is simple but demanding:

If we want healthier men, we have to build systems that keep boys connected—not just once, but over and over, through the years when they’re most likely to slip away.

References

Akande, M. O., Van Eck, K., Wu, X., Perrin, E. M., Hao, L., Matson, P. A., Ozer, E. M., & Marcell, A. V. (2025). Well-visit attendance from mid-adolescence to young adulthood: Who remains engaged? Journal of Adolescent Health. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2025.10.007 (ScienceDirect)

Evans, J., Frank, B., Oliffe, J. L., & Gregory, D. (2011). Health, illness, men and masculinities (HIMM): A theoretical framework for understanding men and their health. Journal of Men’s Health, 8(1), 7–15.

Leone, J. E., Rovito, M. J., Mullin, E. M., Mohammed, S. D., & Lee, C. S. (2017). Development and testing of a conceptual model regarding men’s access to health care. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(2), 262–274.

Mursa, R., Patterson, C., & Halcomb, E. (2022). Men’s help-seeking and engagement with general practice: An integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78(7), 1938–1953.

Parker, K., & Hurst, K. (2025, March 13). The gender gap in teen experiences. Pew Research Center. (Pew Research Center)

Sharp, P., Bottorff, J. L., Rice, S. M., Oliffe, J. L., Schulenkorf, N., Impellizzeri, F., & Caperchione, C. M. (2022). A focus group study exploring challenges and opportunities for men’s mental health promotion. PLOS ONE, 17(1), e0261997.

Teo, C. H., Ng, C. J., Booth, A., & White, A. (2016). Barriers and facilitators to health screening in men: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 165, 168–176.

Faverio, M., Anderson, M., & Park, E. (2025, April 22). Teens, social media and mental health. Pew Research Center. (Pew Research Center)

Forman-Katz, N., Lipka, M., Matsa, K. E., Radde, K., Baronavski, C., & Coleman, J. (2025, December 3). Young adults and the future of news. Pew Research Center. (Pew Research Center)

(Additional foundational works on masculinities and help-seeking, such as Addis & Mahalik, 2003, can be added if you’d like to expand the reference list further.)

About the Author:

Dominick Shattuck, PhD is a public health researcher, community psychologist, and seasoned thought leader whose work advances understanding of men’s health, reproductive health, behavior change, and gender norms. With a career spanning more than two decades, Dr. Shattuck’s research explores how masculinity, health-seeking behaviors, and social systems shape outcomes for men, couples, and communities. His pioneering work includes evaluating mobile health technologies, such as the Dot contraceptive app, conducting the first randomized trial of male engagement in reproductive health, developing innovative health-focused mobile games, and leading the national scale-up of vasectomy services in Rwanda.

At Johns Hopkins University, Dr. Shattuck uses research and monitoring data to strengthen program design and enhance impact across global health initiatives, with faculty appointments in both the Bloomberg School of Public Health and the School of Medicine. He is the CEO of Relational Ground, LLC, where he collaborates with community partners and private industry to expand the reach of evidence-based interventions. A recognized leader in the field, he serves on the Advisory Board of the Men’s Health Network, advocating for improved health outcomes for men and boys and bringing his expertise to national and global conversations on men’s health.

Substack: You can follow along and subscribe to Dominick via the following LINK.