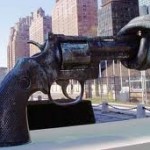

As we try to absorb the tragic events at the school shooting in New Town, Connecticut, various sages have come out of the background to tell us what it all means, and what we can do about it. Gun control advocates – long ignored by our political leaders – have told us, reasonably enough, that ordinary citizens should not be allowed to walk around our civilian landscapes with military grade weapons. The National Rifle Association, after a week of silence, has revealed that guns are not the problem. Instead, we need to upgrade our mental health system, and we need to put strict controls on violent video games or violent movies. Freedom of speech must be curtailed to protect us from crazed gunmen. As for guns, the CEO of the National Rifle Association, Wayne Lapierre, the only protection against “a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.”

As we try to absorb the tragic events at the school shooting in New Town, Connecticut, various sages have come out of the background to tell us what it all means, and what we can do about it. Gun control advocates – long ignored by our political leaders – have told us, reasonably enough, that ordinary citizens should not be allowed to walk around our civilian landscapes with military grade weapons. The National Rifle Association, after a week of silence, has revealed that guns are not the problem. Instead, we need to upgrade our mental health system, and we need to put strict controls on violent video games or violent movies. Freedom of speech must be curtailed to protect us from crazed gunmen. As for guns, the CEO of the National Rifle Association, Wayne Lapierre, the only protection against “a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.”

Freedom to carry weapons must not be curtailed.

These prescriptions have varying degrees of plausibility to different people. We listen to this advice, and find it compelling or impossible, depending on our notions of what seems reasonable. I have a suggestion about why we find fantastic ideas about gun control convincing: we have seen too many action films, and read too many action stories, and we have absorbed their literary conventions. The conventions of the adventure story make us susceptible to believing nonsense about weaponry.

In an action story, just when the villains seem to have triumphed, and the innocent seem defeated, the hero employs violence, and the outcome is precise justice. Somehow the firepower of the hero works to injure the guilty, without hurting the innocent. Violence, especially gunplay, does not produce random results; it does not produce predictable results based on the relative quality of the weaponry and training of the warring sides; violence produces justice. Random looking violence produces justice, as if carefully calibrated by some impartial judge.

The quality of the weaponry does not matter. The hero may have a revolver, and the villains military-grade automatic weapons. Somehow the villains can shoot all around the hero without inflicting a fatal wound. The hero fires his revolver, and disables or kills the villain.

If we read enough adventure stories and watch enough adventure movies, we build a library of possible outcomes in our memories. We cannot help imagining that, in real life as in fiction, as soon as the good guys pull their guns, everyone will be safe except for the villain. So it seems reasonable that an armed guard in an elementary school or a movie theater will make everyone safe from the fellow with the automatic weapon and hand grenades. It even seems reasonable that a scattering of movie goers with their own weapons will somehow find the perpetrator in the dark movie theater without injuring each other, or everyone else. It seems reasonable that the police will arrive and instantly differentiate between the crazed murderer shooting at the public and the valiant defenders shooting back.

That all seems reasonable, because that is what happens in the movies.

Perhaps we are ready to grow up about adventure stories and the real world.