Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in American men after skin cancer. In 2015 alone, there will be an estimated 220,800 new cases of prostate cancer, with a new case occurring every 2.4 minutes.[1]

Prostate cancer can be a serious disease, but a majority of men diagnosed don’t actually die from prostate cancer, they die with it. With early detection, a man and his physician can develop an appropriate management plan that considers his individual preferences and lifestyle choices.

In recent years, there has been strong debate around how we screen for prostate cancer – PSA testing. PSA, also known as Prostate Specific Antigen, is a protein produced by the prostate. PSA levels can rise due to a number of factors, including prostate cancer, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and prostatitis. Before PSA testing was available, it was difficult to detect early stage prostate cancer. By the time the cancer was detected, it had more than likely metastasized to other parts of the body.

PSA testing greatly enhanced our ability to detect early stage prostate cancer, and PSA testing was recommended by the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) to all men over the age of 50. The use of PSA tests increased drastically over the decades, resulting in a parallel increase in the number of prostate cancers diagnosed. The lifetime risk of receiving a diagnosis of prostate cancer nearly doubled with the availability of PSA testing, increasing from approximately 9% in 1985 to 16% in 2007.[2] Subsequently, increases in needle biopsies and men treated for the disease increased as well.

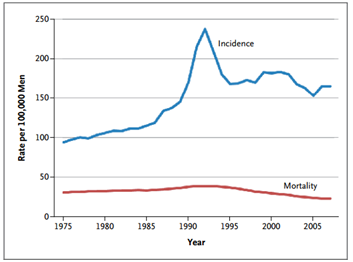

Figure 1: Age-Adjusted Incidence of and Mortality from Prostate Cancer in the United States, 1975–20072

It would seem a logical conclusion that with more men diagnosed and treated for prostate cancer, mortality rates would inversely decline. However, death from the disease remain static. So even though we’re doing a better job of identifying and providing treatment for prostate cancer, we still need better methods and tools to identify the right type of treatment for each patient.

As a result of the overdiagnosis and overtreatment concerns, the USPSTF downgraded PSA testing to a “D”, recommending against PSA-based screening for prostate cancer in 2013. This caused great debate amongst the prostate community, some of which maintained that PSA-testing, in addition to other clinical measures, should continue to be offered as part of routine prostate care.

A summary of the various clinical recommendations and guidelines are found below. Watch out for Part II of this series, which will cover what new technologies and tools are available today to help prostate cancer patients better understand their disease and treatment options.

American Cancer Society (ACS)

The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends that men have a chance to make an informed decision with their health care provider about whether to be screened for prostate cancer. The decision should be made after getting information about the uncertainties, risks, and potential benefits of prostate cancer screening. Men should not be screened unless they have received this information.

The discussion about screening should take place at:

· Age 50 for men who are at average risk of prostate cancer and are expected to live at least 10 more years.

· Age 45 for men at high risk of developing prostate cancer. This includes African Americans and men who have a first-degree relative (father, brother, or son) diagnosed with prostate cancer at an early age (younger than age 65).

· Age 40 for men at even higher risk (those with more than one first-degree relative who had prostate cancer at an early age).

After this discussion, those men who want to be screened should be tested with the prostate specific antigen (PSA) blood test. The digital rectal exam (DRE) may also be done as a part of screening.

Full recommendations here.

American College of Physicians

Clinicians should not screen for prostate cancer using the prostate-specific antigen test in average-risk men under the age of 50 years, men over the age of 69 years, or men with a life expectancy of less than 10 to 15 years.

Clinicians inform men between the age of 50 and 69 years about the limited potential benefits and substantial harms of screening for prostate cancer.

Clinicians base the decision to screen for prostate cancer using the prostate-specific antigen test on the risk for prostate cancer, a discussion of the benefits and harms of screening, the patient’s general health and life expectancy, and patient preferences.

Clinicians should not screen for prostate cancer using the prostate-specific antigen test in patients who do not express a clear preference for screening.

Full recommendations here.

American Urological Association (AUA)

The Panel recommends against PSA screening in men under age 40 years and does not recommend routine screening in men between ages 40 to 54 years at average risk.

The Panel recommends shared decision-making for men age 55 to 69 years that are considering PSA screening, and proceeding based on a man’s values and preferences.

To reduce the harms of screening, a routine screening interval of two years or more may be preferred over annual screening in those men who have participated in shared decision-making and decided on screening. As compared to annual screening, it is expected that screening intervals of two years preserve the majority of the benefits and reduce overdiagnosis and false positives.

The Panel does not recommend routine PSA screening in men age 70+ years or any man with less than a 10 to 15 year life expectancy.

Full guidelines here.

U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF)

The USPSTF recommends against PSA-based screening for prostate cancer (grade D recommendation).

This recommendation applies to men in the general U.S. population, regardless of age. This recommendation does not include the use of the PSA test for surveillance after diagnosis or treatment of prostate cancer; the use of the PSA test for this indication is outside the scope of the USPSTF.

Full recommendation statement here.

Post provided by Genomic Health.

[2] N Engl J Med 2011; 365:2013-2019. Available at https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMcp1103642

[1] Prostate Cancer Foundation, https://www.pcf.org/site/c.leJRIROrEpH/b.5800851/k.645A/Prostate_Cancer_FAQs.htm