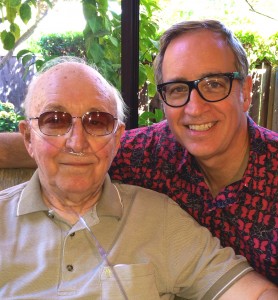

He was one tough old bird. Born to a rural Slovakian family with German roots in the high Tatra mountains for over 1,000 years, he became a blacksmith in his teens, and a craftsman for the rest of his life. He grew up incredibly resilient, self reliant and practical. One of my oldest friends and a career Marine, said of him: “I remember your Dad. He scared the crap out of me when we were little.”

With his large, calloused but gentle hands, he could build or fix anything. He was a master of “manual intelligence,” a man who self worth was defined not by “chattering interpretations of himself” but by the simple fact that “the building stands, the car now runs, the lights are on.” Maybe that’s what led his son to become a surgeon,proud to carry on the “craft” tradition in the family.

But recently, in his early 80s, he became frail quickly. We had embarked on restoring a cool vintage Volvo last year that I had stored in a barn in Connecticut for two decades and this is when it hit me. Our regular conversations about cars, a passion we shared, were now infused with restless anxiety. He was aging fast and didn’t like what was happening. The simple act of breathing was now top of mind. And I saw this once robust man start to pause, and to lean. The two-headed dragon of asbestosis and lung disease, born from a life of welding, began to rear its ugly head.

Vigil in the ICU

My Dad died last week. Quietly. His way. He battled two big cancers in his life and beat them both, and valiantly. Knowing that curing the second of these would be a big proposition, we planned his care all summer. He would come to San Francisco, stay with me and be treated by one of the most skilled surgeons in the land, for there was no room for error. But 7 days after a large, flawlessly performed bladder cancer surgery, his lungs just couldn’t pull it off. Just hours before he passed, right smack in the middle of the ICU at UCSF, he said softly: “I feel like I am home again.”

We stood at his bedside for several hours in the still of the night as his body cooled. During this remarkable vigil, we spoke of love and life, of memorable moments, of life with and without Dad. And because of who Dad was and how he lived and died, our complex lives were clarified in some strange way.

Ranier Maria Rilke, the gifted German poet, once offered advice for young writers. He said that poetry is best written when it arises from deeply felt experiences, not just simply emotions. In his words:

“For the sake of a single poem, you must see many cities, many people and things, you must understand animals, must feel how birds fly, and know the gesture which small flowers make when they open in the morning… You must have memories of many nights of love, each one different from all the others, memories of women screaming in labor, and of light, pale, sleeping girls who have just given birth and are closing again. But you must also have been beside the dying, must have sat beside the dead in the room with the open windows and the scattered noises.”

Life with Dad. Simple, principled, deeply felt and lived in the moment. He always fought the good fight. Now, more than ever, I am inspired to carry on this tradition. In the words Milton Wright, Orville’s father, on his first flight: “Higher, Orville, higher!”

Post originally appeared at: https://theturekclinic.com/my-summer-dad-father-mens-health-death/

Post originally appeared at: https://theturekclinic.com/my-summer-dad-father-mens-health-death/